Why Mediation in Domestic Cases?

James R. Williams, October 2022

Over the last 32 years, I have judged, arbitrated, mediated, or lawyered over 1,500 divorce and paternity cases ranging from no assets and no children to marital estates consisting of several million dollars and cases involving ugly custody disputes. There are no other matters where emotions run higher, or nerves are drawn so taut on a consistent basis as in the domestic arena. The anger and sense of hopelessness becomes so overwhelming in some cases that the parties become capable of otherwise unthinkable and uncharacteristic behaviors. As such, this article is serves as a continuing primer for the lawyer and clients, and a resource to use when preparing for your mediation session.

The popular perception is that criminal cases have equal or more emotional baggage than divorces; however, this is generally not so. Skilled prosecutors acting as the advocate for the government and capable defense lawyers tend to have a buffering effect on the emotion present in criminal cases. On the contrary, even skilled counsel, experienced judicial officers, arbitrators, mediators, and ordinarily sensible parties can fall into the quagmire of a domestic case where there is profound hurt, insecurity, financial stress, betrayals of trust and custody issues. When all of these variables are present and the parties have elevated conflict to a form of combat, the parties suffer, their children become victims, and the judicial system becomes the scapegoat. The brief picture portrayed here is all too common to the experienced practitioner, mediator, or judicial officer. Great strides have been made in the 15 years with the advent of family courts, committed advocates for conflict free divorce, and guardians ad litem representing our children’s best interests. Nonetheless, there remains room for improvement. This is where mediation comes in. A mediation session, perhaps two depending on the complexity of a given case, cannot only serve to resolve the case but also to provide a meaningful foundation for healing of the parties and their families.

As a tool for counsel and their clients, I will outline the steps generally taken in the opening of a mediation session. By attempting to set a tone of understanding and reconciliation, the goal is to begin moving parties to reflect on the better angels of their nature. By outlining this process for counsel, I draw a firm and clear distinction with your competing and complementary job of advocacy. As Elihu Root of the venerable New York firm of Root and Stimson is reputed to have said, “More than half the work of any lawyer worth his salt is telling his clients they are being damn fools and should cut it out.” Root’s pithy statement directly points to our job as “counselors”. This is the tone and message we must emphasize inside the private confines of our offices and conference rooms. Combining your work as a counselor with that of a capable and persuasive advocate who retains the confidence of the client is a critical skill. In the mediation process, advocacy has an important place, but it is here that the role of trusted counselor should be preeminent— particularly in domestic cases. Why is this so? Does not this run contrary to the lawyer’s training and instinct as a proxy combatant? This is so because in domestic cases, absent extraordinary circumstances, winning is a relative term. Persuasive advocacy has its place, and it is a critical one once all rational efforts at resolution short of trial have been fully explored and exhausted by the parties and their counselors. This will invariably lead to some conflict with your clients; however, I occasionally use an old Russian proverb that says, “a mere friend will agree with you; a true friend will argue with you.” While you may not always be your client’s friend, the same principle applies. You have a duty to be candid with them at all times even if they don’t like what they are hearing. Most clients will subsequently thank you; those that fire you may later realize the error of their ways; and for those that don’t ultimately realize their mistake, you likely didn’t want or need the as clients.

For the last decade, I have frequently met in introductory sessions with each party in a private caucus space. My experience has been that joint sessions too often set a toxic and counterproductive tone for the mediation. The opening session is critical to a successful mediation for any number of reasons. Two of the most important are as follows: first, it is the mediator’s introduction to the parties;[1] and second, the better mediators use this opportunity to persuade the parties that this process is beneficial, is one in which they can feel safe, and offers a forum that has a good chance to resolve the dispute. It is this second reason that is the focus of this article. Ideally, by this point counsel in a domestic case will have provided a pre-mediation statement and spreadsheet outlining the property and custody issues so that I have a feel for the case and do not need, or even desire, opening statements or arguments from counsel. In contrast to other civil cases, my experience has been that if counsel insists on an opening statement in a joint domestic mediation session, it tends to poison the well.[2]

After we have each party situated in their conference room and introductions are made, I proceed to describe the process. While this sounds self-evident, and probably is to most of us, this stage has a disproportionate impact on whether the dispute will get resolved in mediation. Therefore, while this may seem like a perfunctory exercise, in the domestic dispute, it lays the foundation on which we build a successful mediation. For purposes of this discussion, I am going to assume that the parties have minor children, and that custody and parenting time are at issue.

Opening Session and Description of Process

The following narrative is a description of the information communicated in the opening session. It is conveyed in a conversational tone designed to create trust but with enough conviction to set expectations, to establish boundaries, and appeal to reason. Depending on the circumstances, these messages often need to be repackaged at various times during the later caucus sessions using concrete examples that have arisen as the mediation progresses.

Mediation is designed to give parties an opportunity to communicate with each other through a trained mediator in an effort to reach a mutually agreeable resolution to the divorce and all of the issues involved. While it is an opportunity to be heard and to listen to the other side, it is not a courtroom, and the mediator cannot force you to do anything that you do not wish to do. Ultimately, the mediator is a facilitator of communication between the parties, their lawyers, and the children’s court appointed advocates. This exchange involves both talking and listening. The listening part is equally important in that, as Winston Churchill said, “…. even those we think fools occasionally have a worthwhile idea.” Finally, while you cannot be forced to agree, once we do reach an agreement, it is reduced to writing, signed by the parties, and it is enforceable.

As any experienced lawyer knows, the majority of domestic cases settle without the necessity of a final contested hearing. Some cases need to be tried, and perhaps yours is one of those cases, but more likely than not, it is like most other divorces and should be settled. The judicial system recognized that most of these cases were resolving outside of court but were often settled on the very eve of trial—the proverbial settlement on the courthouse steps. Mediation was adopted in 1991 as an alternative designed to move this settlement discussion to a point earlier in the litigation and to place the parties in a professional setting where they have to focus intently on resolving their differences.

In many instances, your trial judge will order you to mediation. The parties will often view mediation with suspicion and assume that the chasm between them is so wide that mediation could not possibly be successful. In explaining this to the parties, I inform them that mediation has an extremely high success rate. In fact, approximately 9 of 10 divorces settle before trial. In those cases, many were resolved at mediation. By explaining this to the parties, I hope to convey that their skeptical initial attitudes are a common denominator in these cases. Further, by highlighting the success rate, I challenge them to be just as successful and not to be an outlier or to fail to match others’ successes.

The brief history of Indiana’s adoption of mediation illustrates that the judicial system cares about resolving cases and is not simply a venue for the parties to joust in a courtroom. By formally recognizing mediation as an alternative means of resolution, the Court is not only attempting to preserve judicial resources, but also the resources and health of the parties. I explain that as a third-generation lawyer, I am very much in favor of lawyers being paid and making a living; however, good lawyers who do everything possible to solve their clients’ problems short of trial will have plenty of work and make a perfectly respectable living. This is where we establish that continuing to fight it out has a measurable and significant financial cost. Attorneys’ fees, expert expenses, and continued bills related to the uncertainty associated with lack of resolution are just three examples of the punishing financial burden imposed by the fight.

The other set of costs are even more punishing but are largely incalculable. These are the immeasurable emotional costs borne by the parties and inflicted on their children. The human body and psyche are not built for prolonged high intensity conflict that is often present in divorce cases. The primitive part of our brain where the ‘fight or flight’ defense mechanism lives was designed to protect us during brief periods of intense and threatening danger. When it works overtime, as it does when parties are going through a contested divorce, the adrenaline produced has a malignant kindling effect on both the human body and psyche. Fatigue sets in, and we grow depressed and anxious. The trauma of life causes the delicate balance of our minds and bodies to malfunction. We grow suspicious, cynical, bitter and have any number of physical behaviors and symptoms including headaches, difficulty sleeping, substance abuse, heart palpitations, angry outbursts, and poor nutrition, just to name a few. These are the immeasurable costs. They are not capable of ready measurement as are the financial costs, but they are real, they are damaging, and they will not go away while the dispute continues.

Most all parents want to think that they are the only ones suffering these intangible emotional and physical costs— that they are placing their children outside or above the fray. This is a delusion, or perhaps more kindly, an illusion. Even in a low conflict, uncontested divorce, the kids will have feelings of insecurity. The world they know is no more. This is a tough realization at any age. In a high conflict divorce, even with parents attempting to shield the kids, this sense of insecurity is much more acute. More disconcerting, it can become chronic and stay with the young person into adulthood and create a higher risk of depression, anxiety, or attachment disorders. Again, I cannot measure these costs in a precise manner; however, they are real, they are damaging, and the children cannot begin to heal while the dispute persists.

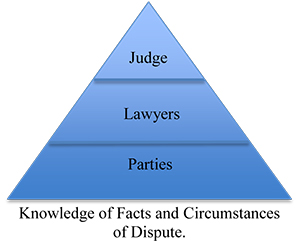

The imposition of these measurable and immeasurable costs should be enough to spur any rational person towards compromise and resolution. Alas, many parties in the midst of a difficult divorce are not rational. Fortunately, there are other compelling reasons to reach a settlement at mediation. Litigation is uncertain. If I had a dime for every time a party said that he or she had no doubt about a given issue and is prepared to go to trial, I could come close to retiring. That is probably an exaggeration, but the sum would be tidy, nonetheless. In expressing the uncertainty of litigation, I use a diagram that I call the Litigation Triangle. It looks something like this:

The Litigation Triangle is a simple method to illustrate the uncertainty of litigation. I preface the description of the triangle with the acceptance that each party has capable counsel, the judge in the case is hardworking and fair, and I trust that both parties would make every effort to be good witnesses. Notwithstanding these factors, human nature tells us that they are not perfect communicators;[3] their lawyers are skilled but not perfect communicators; and the judge is a skilled but not a perfect listener.

Following this preface, I point out that the base of the triangle represents the cumulative knowledge and familiarity with the facts and circumstances of the dispute and the marriage. As such, the breadth of the triangle at its base illustrates that the parties have the most thorough and intimate knowledge of the facts. By virtue of how our system is built and the triangle closes to its top point, the lawyers and other witnesses will know less than the parties, and the judge will know less than the lawyers. In a 20-year marriage, a lot can happen in the way of property acquisition and disposition and in the rearing of children. The lawyers will do their best to learn everything they need to in order to present your case and the judge will do his or her best to listen carefully to the evidence and to render a fair and just decision. However, all of this depends on the imperfect communication and listening skills of each participant. The lawyer has other cases and demands on his or her time and the judge may have in excess of 2,000 cases on the docket in a given year. This is not to belittle or call into question anyone’s skills, integrity, or commitment, but simply to highlight that litigation has all of the limitations, imperfections and uncertainties that accompany any human endeavor.

As such, no outcome is guaranteed on a given day. Moreover, absent demonstrable legal error that is capable of being remedied on appeal, you must live with the result. This is not your result. It is the judicial system’s result. It is a result imposed on you by the good faith and advocacy of the lawyers and the wisdom of the judge. It is a result that is informed by the law and the evidence. BUT, it is not your result and you must live with and abide by it under the punishment of contempt for failure to do so. Wouldn’t you rather own the result? If you compromise and settle, it won’t be perfect, but it will be yours. It will be certain, and you can stem the financial hemorrhaging and mitigate the emotional torment of both you and your children. As I tell people, the best settlements leave both parties equally unhappy but pave a certain and lighted pathway forward that is untethered from the disadvantages, uncertainties, delays, and costs inherent in prolonged conflict and litigation.

So why mediation? A simple and common aphorism sums it up as well as anything. “A bird in the hand is better than two in the bush.” The costs and heartaches reaching into the bush rarely leads to catching both birds, and the attempt to catch them both leaves you spiritually and financially poorer. The key is convincing the parties that this time-tested maxim is full of wisdom and helping them to reach a mutually agreeable resolution.

[1] Keep in mind that in a domestic mediation, this will likely be the parties’ first experience in this setting. Accordingly, their anxiety is already heightened and they are not sure what to expect. The best introductions help to ease this natural anxiety.

[2] Likewise, as a former judicial officer, my experience was that an award of attorneys’ fees at the Provisional Order stage frequently had the effect of heightening one or both parties’ anger and frustration thereby hindering later efforts at negotiated resolution. Therefore, absent clear financial inequity or agreement of the parties, my approach was generally to defer awards of attorneys’ fees to the Final Hearing. In this regard, it remained a distinct possibility but was not going to have the effect of a hand grenade at the outset of the case.

[3] As they are in the middle of a divorce, it is a fair assumption that there has been a failure to communicate—with a respectful nod to Strother Martin’s character in “Cool Hand Luke.”

James R Williams is a partner at DeFur Voran. He is a certified civil and domestic mediator and is listed as a private judge by the Division of State Court Administration. He served as judge of Union Circuit Court from 1998 to 2005 and as senior judge until 2008.

James R. Williams